Before I wrote stories for a living, I had a list of misapprehensions about as long as my arm. Like “if you sell a book, you can quit your day job.” Or “the really hard part is writing the book.” I’m getting over my naivete, but it’s like alcoholism: an ongoing process of recovery.

One of the longest standing illusions was that writing was an essentially solitary job. The author sits in her high castle, consults with the muse, a couple first readers, and that’s about it. Turns out, not even close. At least not for me.

The fine folks here at Tor.com have allowed me to come in and do this little guest blogging gig, and when I started thinking about what sorts of things I’d want to chew over with all y’all, I kept coming back to issues of collaboration. So, with your collective permission, I’m going to hold forth on and off for a few weeks here about different kinds of collaboration and how they’ve worked out (or failed to work out) for me.

Some of this is gonna be a little embarrassing.

I’ve done a lot of work with other people—co-authoring books and short stories, doing comic books, critique groups, working with editors and agents—but I’d like to start off by telling stories and gossiping about the biggest, messiest, strangest collaborative project I’ve ever been part of.

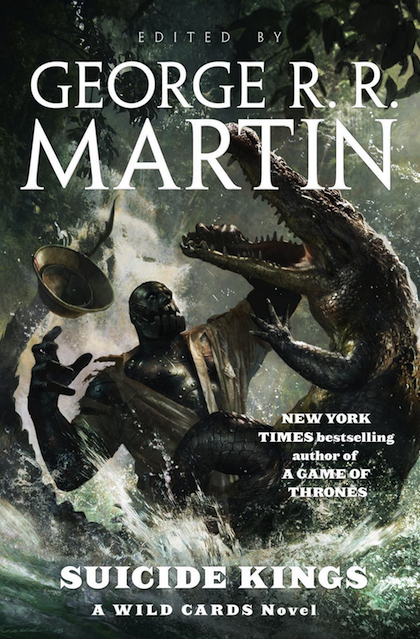

Let me tell you about Wild Cards.

I came to Wild Cards first as a reader, because it started in 1987, more than a decade before my first professional sale. It was a shared world series like Thieves’ World, only with superheroes. It was headed up by George RR Martin, who was at that point the guy who wrote for the new Twilight Zone series and the Beauty and the Beast show with the lady from Terminator. It had stories by Walter Jon Williams and Roger Zelazny and a bunch of other folks. And its superheroes were folks like Golden Boy who failed to stop McCarthyism and Fortunato, superpowered pimp. This was the same era when Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns were changing the face of superhero fiction. Wild Cards was right there with it, and fresh from high school and heading for college, so was I.

There’s a middle part where the series goes for 15 books over the next decade or so. I’m going to skip that. Then there was a book called Deuces Down where I got to write a story. I’m going to skip that too.

When time came for George, who was now wearing his American Tolkien drag, to put together a new triad, I was invited to come play. Because of that Deuces Down thing I did last paragraph, I’d already signed an inch-thick wad of legal documents and become part of the Wild Cards consortium.

It went like this.

We were going to restart the Wild Cards story, not by rebooting it a la Battlestar Galactica, but by getting a stable of new characters and new story lines and writing the books with the express intention of making it something that anyone unfamiliar with the previous 17 books could read (yes, it was up to 17 by then). Call it Wild Cards: The Next Generation. So George opened it up and we started throwing characters at him. Sometimes they were well thought-out, with character arcs and carefully planned backstories. Sometimes they were sketched on the back of a napkin. (“He can make people sneeze by looking at them.”)

Some characters made the cut, some didn’t. After a huge meeting in a secret location deep in the heart of rural New Mexico, we started getting an idea of what the story of the three books was going to be. The central conceit of the first book came from a throw-away line in one of Carrie Vaughn’s first characters. The character didn’t make, but the reality show American Hero did.

This is the first place—the only place, really—I’ve ever “pitched” a short story. Usually, I write them, and either an editor someplace likes it or they don’t. This was my first real hint that Wild Cards wasn’t really like writing a short story. Or anything else. In it, we said what story we wanted to tell along with an idea of how it would fit into the overall book.

George picked the starting lineup, gave us some ideas about how to make the stories fit together (moreso to me, since I got the dubious honor of writing the “interstitial” story—sort of the mortar between the bricks of other stories), and we were off.

Imagine a race where all the runners are blindfolded and the layout of the track is described to them. We called each other, asked questions, tried to coordinate. (“So, what’s the last line of your story?” “Okay, in your story, are these two friends? Because in mine, they hate each other.”) And in the end, we delivered up our manuscripts to the man.

They were a mess. Of course they were a mess. Some fit together, some didn’t. Some stayed in, others didn’t. George sent us wave after wave of notes. Slowly, the whole manuscript came together until each of us had a story that didn’t quite meet our first dreams for it, but added up to something bigger even if we couldn’t see it yet. And we were done.

Except of course we weren’t.

Shared world projects are unlike anything else I’ve ever seen in that the writers are encouraged to play with each other’s characters, make connections, create a sense of civilization with all the messy, complex relationships that carries. But playing well with others isn’t easy, and one of the hard-and-fast rules of the game is that when you use someone else’s character, they have to approve it. (Just this week, I looked over a scene David Anthony Durham wrote using a minor character I created—the one who can make people sneeze, among other small, sudden biological spasms.) So we tracked down everyone whose approval we needed, negotiated with them to make the characters true to their visions of them. And then we made the corrections, sent them to George, got another round of notes.

And even then, we didn’t really know what the final product was going to look like until George had cut things up, rearranged them, and put them all together again. And then, once the book was done, the whole thing started over again, with new pitches, more characters, and another lineup for the next book carrying through some plotlines, finishing up others.

Like me, Carrie Vaughn was a fan of the series before she was a writer. She said that the hardest thing about being in the magic circle of the project was seeing all the cool things and nifty ideas that didn’t make it into the book. For me, the hardest thing was working on something where I could make out the limits of the final project.

The best metaphor of shared world collaborations is something like a rugby scrum. Everyone pushes in their particular directions, sometimes pulling together, sometimes against each other, but always with tremendous effort, and the rough parts are just as interesting, productive, and important as the ones that go smooth. Plus sometimes you lose a tooth. I think that if you asked the other writers who were in the books I’ve done in this project, they’d report an entirely different experience from mine, or each other. There are so many people and perspectives and styles and visions, there could be a dozen different and apparently mutually exclusive reports, and all of them true. Which is a lot like the Wild Cards universe we wound up writing.

Next up: Co-writing a novel with one (or two) other writers.

Daniel Abraham is the author of the Long Price Quartet (A Shadow in Summer, A Betrayal in Winter, An Autumn War, and The Price of Spring, or, in the UK, Shadow and Betrayal & Seasons of War) as well as thirty-ish short stories and the collected works of M. L. N. Hanover. He’s been nominated for some stuff. He’s won others.

As much as I love the WC series, I would really appreciate if GRRM would put down some of his side projects and finish Ice and Fire… or at least Dance with Dragons which he’s been working on for 5 years now :(

Welcome to the blogging, Daniel! I’ve been hoping to see something from you on tor.com.

I’m sort of fascinated by the Wild Cards idea because I love the concept and admire the collaboration. I came to the series as a reader from the same sort of perspective that George and others approached it as a writer: as a gamer.

Anyway, I really enjoyed learning about how the collaboration came together because I’ve always wondered about it. I’ll be looking forward to your later posts.

Daniel, thanks for this bit of insight into the process. Like you, I was a fan of the series well before I started writing, but I always wondered how the whole thing came together and how the pieces were made to fit. It’s been something that I have considered trying one day (though maybe I shouldn’t).

I need to catch up with the new books, but looking forward to it.

OK, Wild Cards look cool and I’ll be sure to pick it up one of these days. On a related note, what the hell is a Scientologist ad doing on tor.com ?. I am frankly shocked and appalled to find such murderous bullsh*t on this blog I respect. You of all people should know about the power of words ; you are endorsing a cult.

Plus, Hubbard is globally recognized as a terrible SF writer – kind of ironic to find him advertised on a blog that deals at least in part with criticism and reading recommendations.

I really hope you will do something about it.

Oh, Wild Cards…

Collectively, you all did a fantastic job with the Next Generation of Inside Straight and Busted Flush. I’m still catching up on the older stuff, but your goal of making the series accessible to folks who hadn’t read the previous seventeen was absolutely achieved.

Jordo @@@@@ 1: I don’t think this is the place for that.

Yeah, the next gen stuff is great — definitely lives up to the classic books. I’m a big Wild Cards fan and it was neat to get a look under the hood like that.

I liked the first two Wild Cards books very much, but the later ones become more and more violent for violence’s sake and by about book 7 I began to think I was reading a Gor book. I hope that the series, if it continues, can get back to what authors like Zelazny, Waldrop, and Martin himself were doing at its start.

jmeltzer: Yeah, I feel your pain on that one. We talked a lot about the darkness in the Wildcards books and how it got deeply off-putting. I have some ideas about how (and why) that happened.

What I’ve seen with the new books is that — while they’re still plenty dark, and there’s violence and sex and people sometimes use the full extent of vulgarity offered by our fine language — they’re more *humane*. I put in Bugsy in the new books specifically to have the Han Solo/Plucky Comic Relief guy, and the work Tregillis and Farrell did in Suicide Kings took something that could have been unbearable and gave me a story line that offered humanity and hope without being remotely Pollyanna.

And with some of the other new writers coming in — David Anthony Durham, David Levine, Cherie Priest, Maryann Monhanraj all come to mind — I think we’re going to be seeing some very good work in coming books too.

If you stopped reading Wildcards because they were too grim, brutal, and punishing for not enough payoff, you’re powerfully not alone. We were all trying to tack away from that when we took on the reboot.

Wow, I still have my GURPS WildCards around somewhere. Had no idea that universe had such a big scope.

Oh my god, there’s a GURPS?

MUST HAVE.

Wild Cards and Discworld are on my “To get at all costs” list.

Thanks for the insight, Daniel (Amusingly, you share both first and last names with a friend of mine who has recently started reading GRRM). Is there a way you could post other people’s Wild Cards stories (The ones they have about Wild Cards, not the stories that were published in the Wild Cards books), or at least force them to post them, or bash their heads against a keyboard hoping something mildly like a story comes out? I mean those that are different than yours.

Jonathan Hive is my favorite Wild Cards character, by the way. Didn’t come off as comic relief at all.

I love how you’re all good writers individually.. and managed to create a great cohesive book collectively.

Because that doesn’t always happen. Especially in Hollywood ;)

I imagine it’s also a fun process working as a group (rather than stewing alone in the writer’s office for the whole journey), although not without it’s share of headbanging, aha.

I wonder if writers are more likely to finish collaborations than solo works.

GRRM seems to be doing a lot of collaborations lately….hrmmmm

Daniel,

I’d like to see your views as to why Wild Cards drifted in a very dark direction. It’s true that, when compared to the first handful, there was a marked shift in tone as it went along. This was endemic in the comics of the era, and I’ll suppose a part of it was in response to the political climate and current events in the 80’s.

I didn’t find it really off-putting myself, but there’s certainly room for more the light-hearted narratives early on. I do think the latest triad is doing a pretty good job of mixing the tone up a bit.

I wrote in about the Scientology ad myself. Though after I wrote, I noticed the little “Google Ads” marker in the corner. So I would guess that Tor.com probably didn’t even know the Scientologists were targeting them until they started getting feedback about it.

ANYWAY, on the subject of the actual post at hand. I’m a little surprised, though I shouldn’t be I guess, that nobody has brought up collaborative writing on the Internet yet. There’s been a heck of a lot of it: some terrific, some good, some bad, some execrable.

Kind of like the proverbial chocolate and peanut butter, the Internet and collaborative writing go hand in hand. This was especially true back in the late ’80s to early ’90s when college students first started coming onto the ‘net en masse, finding others who shared similar fictional interests, and writing stories together.

And since these stories were delivered electronically, the “e-book” was born, years before anyone even coined the word.

I participated in a number of those forums myself, and wrote about them in a series of columns for TeleRead called “Paleo E-Books”. For those interested in more detail, I suggest checking them out. The archives of a lot of these shared universes are still around, and some of them turned out to be amazingly prolific (not to mention remarkably good).

Because these stories were posted simultaneously on e-mail or Usenet-based lists as they were written, rather than gathered up and edited for later publication, the nature of the collaboration was a bit more haphazard than the process described above for Wild Cards.

In most cases we just did our own thing—there was not any editor or coordinator such as Martin, except in cases where a crossover event happened. Characters tended to mind their own business, and might mention things happening in other stories currently being posted, but any actual appearance or use was cleared with the characters’ owners on a one-on-one basis.

But for those crossover events, Abraham’s description definitely strikes a chord. I remember what it was like both working with other writers and coordinating my own crossover events, and it was often a bit hectic—but the results ended up being worth it. And all we really had in the way of coordination tools back in those days was e-mail and text chat (and it was uphill, in the snow, both ways!).

With the advent of tools such as wikis, EtherPad, and Google Wave, collaboration has only gotten easier, so it should not be surprising there are more shared-world settings out there on the Internet than ever before, for all sorts of fictional interests.

One of my favorites, and one to which I’ve contributed a few stories, is a furry-transformation setting called “Paradise” (named for “A Kind of Paradise”, the story that originated the setting).

The premise is that some unknown phenomenon is causing people to turn into anthropomorphic animals and sometimes change gender (but only other people who have been thus changed can see them that way, at least at first). Some of the stories are fairly bad (in fact, I advise skipping the first two in the chronology and starting reading with “Made Alone”, which kicks off a series of stories by one of the setting’s best writers), but the vast majority of them are amazingly well-written.

I guess the setting became so popular because the idea of hidden “otherness” struck a chord with people who feel that they have a part of them they have to hide away from most people because almost nobody else would understand it. (Which would be probably most of us at one time or another.) And it provides a way for people to make “Mary Sue” or semi-“Mary Sue” stories plausible given that the whole point of the setting is the effect these changes have on ordinary people. It also helps that most of the writing there is so good it makes you want to be a part of that world.

The nice thing about Internet shared worlds, when they work, is that it narrows the separation between writer and reader. Writing fanfic of published settings you love is generally frowned upon by the writers of those settings—but in an Internet shared world, all you have to do is email or chat to the setting owner, “Hey, I had this great idea…” and before you know it you’re one of those writers yourself. And if you get a good enough rep with what you write, you might even be able to cross over with other writers in the setting from time to time.

So, for people who are interested in working in a shared setting, look for some of the Internet shared universes currently going on. They can be a lot of fun.

(Yeah, yeah, I know. “TL;DR”. :)

Thanks for the post, Robotech_Master. That was an interesting read, if for nothing else than the nostalgia of seeing Usenet being discussed so much.

To me, the most exciting thing about this blog is the implication more Wild Card books are on their way! I’m *very* excited to hear that and hopefully most of the writers in the newest triad will continue to participate!

I hope Mr. Martin doesn’t pull a Jordan on us and depart before finishing WILD CARDS.

As well, I don’t generally follow American football, but his not-a-blog is an invaluable source of talking points with my Yank coworker.

My friends and I are all quite a twitter vis-a-vis this post, Mr. Abraham. I hope you’re involved in subsequent volumes, but do hope it doesn’t impact your own career. I might be picking up your complete Long Price Quartet now that WILD CARDS has illuminated you to me. ;)

Don’t stop writing, good ser.

Hey, folks. Someone asked for other perspectives on collaboration — I’ll have a story in the next Wild Cards book, so here’s my quick experience.

I’ve tried three methods of collaboration so far:

a) I tried to write a joint story with writer/editor Jed Hartman (of Strange Horizons fame, and whom I am romantically involved with). It started out splendidly, with lots of fun brainstorming and throwing of ideas around, and some quick drafting, and quickly ran up into a massive wall of fail, when Jed and I started arguing mightily, stuck rigidly to our own ideas about the story, and ended up in tears. That story, needless to say, was never completed. Luckily, the relationship survived, but perhaps the lesson learned was that writing with the people you sleep with is a risky endeavor. It was also much more work than just writing a story by myself.

b) I participated in Frank Wu’s _Exquisite Corpuscle_ anthology project, where writers and artists wrote work inspired by others in the project. I was handed a Ben Rosenbaum story to read, and wrote a poem in response to it. Someone else got my poem, and made some art in response to that. And so on. None of us got to see the rest of the project until publication. Super-fun, and an interesting result, I think.

c) And now this Wild Cards book. Brainstormed some characters, George liked ’em, drafted a storyline, he suggested some changes. I agreed, wrote the story and sent it in; some time later, George wrote back saying that about three-quarters of my story wouldn’t work anymore because of other elements in the book (in particular the way other people’s characters have developed since original conception). Argh. George said, could I please save that material for a later story, draft a basically new story with my same characters in a way that’s a better fit for the book, and oh, make it sexier, please (a reasonable request, given that one of my characters works in the sex industry). And I said, roger wilco, and that’s where I am right now, revising. It’s a frustrating process in some ways, but also fun — can’t wait to see the finished product!

He really should write A Dance With Dragons.

I’m sure Wild Cards is wonderful and all, what with the furries and superpowers and such, but I’d really rather he finish aSoIaF. Or, at least, acknowledge that it exists from time to time. If he’d even take time away from his pizza and football to tell us “Hey, I have writer’s block…it might be a while.” I’d be mollified.

It’s been estimated that the amount he has blogged about football (on his “Not a Blog” that he “doesn’t have time to write in.”) could be bound into a full length novel, and yet he can’t be bothered to write his best selling series. And on top of that he has an assistant screen comments so that all he has to read is lavish praise!

What an absolute f***er!

Okay, guys. I respect that y’all want George to finish ADwD. I’m looking forward to it too. My post wasn’t about A Song of Ice and Fire; it was about collaborating in a shared world.

George’s name is going to come up in at least one of the other collaboration posts, and that’s *also* not going to be about A Song of Ice and Fire, because I don’t work on that project.

If you want to call George names, it’s a free country, and you get to. While we’re here, I’d appreciate it if we could keep to the subject at hand.

Deleted comment #18 because there was nothing in it but vile vitriol.

@21, 20: As Daniel says, this post isn’t about ADwD–please keep to the topic, and save the anger for another, more appropriate venue.

Maybe George should collaborate with someone to finish his flagship series. I’m not being smarmy, I think it’s a good idea since he can’t seem to put any effort into it himself. Maybe working with someone else would motivate him.

And Daniel, please understand: Any communication with him is screened so aggressively that he likely doesn’t see anything resembling criticism because anything negative, respectful or not, is deleted before he reads it. I figure that he’s so sheltered that he has come to believe fans of I&F are happy with his current level of no progress at all, and it can’t be helping his motivation level. Any mention of him on other sites, related to I&F or not, is going to bring out people who are frustrated with him because they not only don’t have a finished story to read, they can’t even communicate their frustration to him. Myself included.

Some comments are going to be nothing but vitriol, because for the last several years GRRM has shown what appears to be nothing but contempt for the fans of I&F. But maybe, just maybe, some comments like these on unrelated blogs and websites might break through the Great Censorship Wall he’s surrounded himself with, letting him know that many people are not happy with him right now.

He obviously needs an infusion of motivation, somehow.

@CheDelias 24

Once more: not the appropriate venue for this, regardless of whatever rationale you want to use to justify it. Further OT posts will be deleted, no warning and no questions asked.

I actually prefer Wild Cards. The only other shared universe I’ve liked were the Liavek books, way back when.

And wasn’t there something about GRRM not being your bitch?

Further comments consisting of aSoIaF whining will lose their vowels. You’ve been warned.

I’m a little disappointed nobody’s been interested in discussing the nature of collaborative writing on the Internet that I mentioned earlier. It’s fascinating to me, the way that the Internet makes multiple-author collaboration and cooperation easier than ever before.

I recently posted an interview I did with the tech admin of Shifti.org, the website where the “Paradise” shared universe I mention is hosted. I think it’s possible that this kind of site might be one aspect of the future of storytelling. There just needs to be a way of separating the good stuff from the slush.

@19,

Thanks for sharing that! The collaborative process can be really different, depending on the collaborators and the intentions behind them.

@28,

I find the subject interesting, but I’m afraid I can’t really offer up much to discuss. I kinda-sorta do this already, if one counts roleplaying via text-based mediums a form of collaborative writing. It is, but the form and intention behind it is, I think, pretty different from the kind of collaborative writing you’re talking about.

I do wonder at how these ad-hoc collaborative stories that used to be/are being generated on the Internet are managed or “controlled”. With Wild Cards, GRRM is obviously the person managing and fitting everything together. Same thing with Frank Wu’s book mentioned @19. Perhaps some other shared-world uses a completely different process.

I’m trying to remember what I recall of the Medea shared setting, which I read years ago. I’m sure Harlan Ellison explained something of how it was decided who would write what. Though, IIRC, the stories stood very much alone.